This tweet proposes a pretty useful definition of postmodern:

postmodernism is incredulity towards metanarratives

So should we be skeptical of metanarratives?

Yes, they get us to do things against our own interests. But we also need them for coherence. So rather than giving you a straight answer, let me take you on a detour.

The Detour

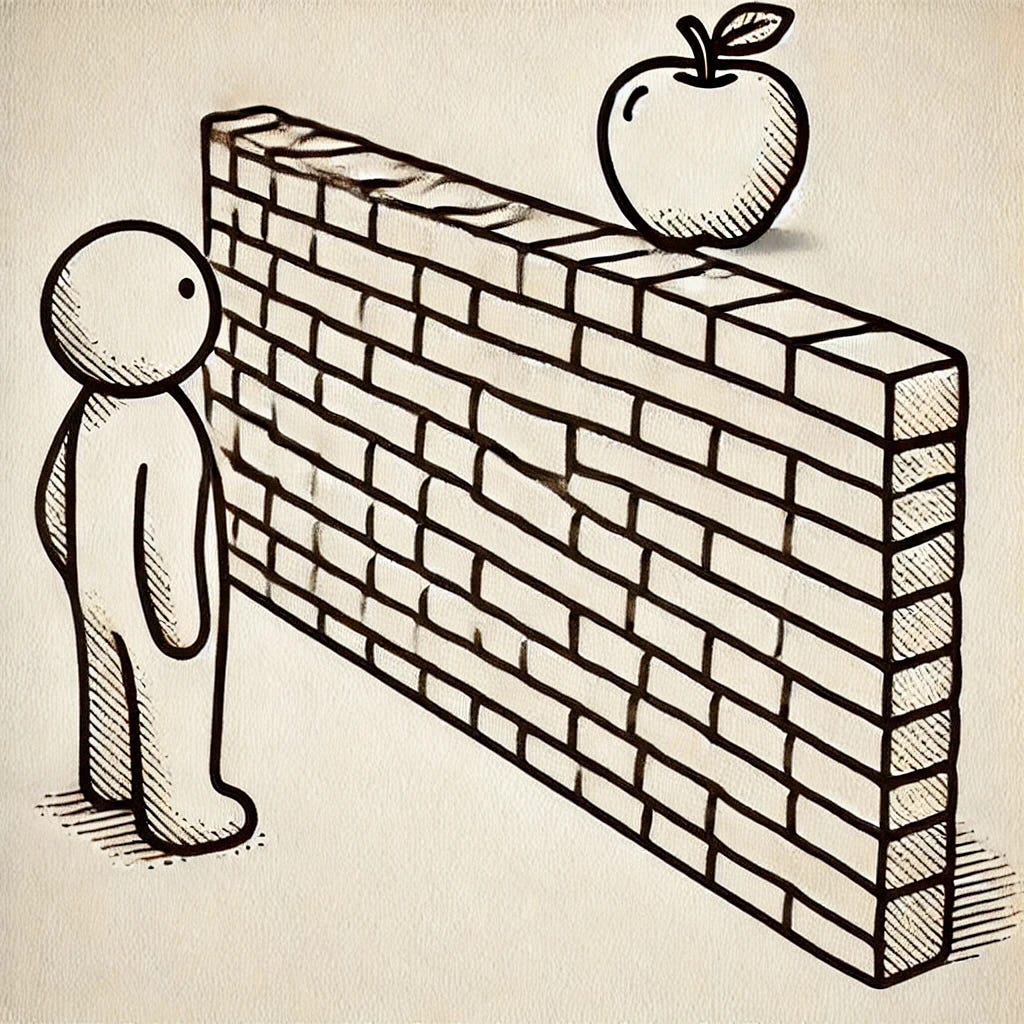

Imagine an animal that is only able to move in a straight line toward food when it sees something to eat. As long as each step brings it closer to its objective it does fine. But as soon as there is an obstacle, it cannot bring itself to go further away from the objective in order to reach the end goal.

This is a being without a narrative.

Of course, most animals are able to navigate obstacles. Rats, for example, can navigate quite complicated mazes to reach food. And they don’t have narratives (at least I think they don’t). They have some pretty sophisticated programming that allows them to turn left and right instead of continuing to bump up against walls. We can imagine this programming makes them feel like they are going toward their objective when they, for example, take a left turn in a maze or go around an obstacle.

A narrative is like this. It influences our local decision gradient, but it is much more flexible than the programming of a rat. And narratives enable much more complicated behavior than we ever see from rats.

Coordination Problems

There are two important categories of complicated behavior that programming (and narratives) enable. The first has to do with enabling coordination with our future. This is like going around a wall. We model a path to an objective and perform some kind of reparameterization of our decision space so that following that path feels like it’s moving forward. In the short term this can get us farther from our goal from a purely physical perspective, but in the long term it often ends up being more effective. In some cases we have to give up something in the present in order to get a bigger payoff in the future, like someone who puts a small fish on a line to catch a bigger fish.

Newcomb’s paradox is an interesting (although admittedly unrealistic) illustration of how the ability to coordinate without our future self can impact outcomes.

The second kind of complicated behavior involves coordination among multiple people. This is the classic collective action problem. We can achieve more by working together, but we can only do this if we have “trust”, that is, some kind of programming or narrative that allows us to take an action that only makes sense if we can rely on other people. The prisoner’s dilemma is a special case of a collective action problem. If two prisoners can trust each other to do something “irrational” i.e., something that doesn’t make sense without trust, they can get a better outcome.

Eigenvectors

Eigenvectors are pretty interesting. An eigenvector of a matrix is a vector that, when multiplied by the matrix, yields a multiple of itself, i.e.,

The value of the multiple, λ, is called an eigenvalue. When a matrix has multiple eigenvectors, sometimes one eigenvalue is bigger than the others. So let’s say we have the simple matrix:

It has two eigenvectors:

If we take any vector and keep multiplying it by A, the top value will stay the same and the bottom value will keep doubling. Eventually, the bottom value will dominate.

Now imagine that we have a vector of states in the universe, including values representing individual people as well as abstract things like “human” or “frog memes”.

Now think of physics as something that just moves the thing-state-vector along. Some values in the vector will persist for a while (i.e., some things survive) and some will get bigger (i.e., they reproduce). Values that keep getting bigger can be called replicators (life?). They are kind of like the eigenvectors of the universe. The things that reproduce the most are like dominant eigenvectors.

Superposition

The reason for that little detour is that for those of you familiar with vectors, one of their main properties is that they can be added to each other. Each vector can be viewed as the sum of a bunch of simpler basis vectors.

In the short story about eigenvectors, I said that the universe can be viewed as a bunch of states representing different concepts, some of which are replicators. But we can even view ourselves this way. Each of us is a legion of replicators: recurring structures like atoms and molecules, DNA, brain waves, memes, and of course, metanarratives. Our local decision space is influenced by all of these things just like a local electric field is the result of many neighboring electric charges. We have many spirits, many replicators large and small that all influence our behavior.

One of my favorite books (which I mention often), The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, describes consciousness arising from the interaction of our brain hemispheres. But really, we could view our consciousness as arising from the interaction of an innumerable number of different replicators.

A metanarrative is one of these replicators.

Narrative and Metanarrative

But how is a metanarrative different from a regular narrative?

To be honest, I don’t love the word metanarrative. If you google it, two definitions come up:

The prefix “meta” makes me think more of the first one. That is, a metanarrative is a story that is saying something not just about the characters, but about stories themselves — an ironic story.

But the second meaning has more to do with our current story. That is, a metanarrative is a story that encompasses other stories, like a superstory that contains and informs other stories.

Even with regard to the second definition, I think there is some ambiguity. In a episodic tv series, there is a formula for each episode and an arc across the season. The term metanarrative is sometimes used to refer to both. Like the hero’s journey is more of a formula for many episodes, whereas the religious framing of creation-life-apocalypse is a season arc.

Postmodern theorists are skeptical of season arcs, not ironic storytelling or formulaic episodes.

A Big Problem with Metanarratives

The reason why we should be skeptical of metanarratives is simply that they don’t help us achieve our goals. Unlike the rat programming that helps him get some food at the end of a maze, metanarratives don’t really help us get food (with some exceptions discussed later). Rather, they offer up new goals that are supposed to be bigger than the ones we want as individuals — eternal life, national glory, maximized utility, etc.

This is why metanarratives can be used to get us to act counter to any or all individual goals. In particular, postmodern theorists are often concerned that elites use metanarratives to get plebs to sacrifice themselves in war or alienated labor.

Actually, it isn’t just postmoderns who are worried about this. In fact Jordan Peterson, who would definitely deny being postmodern, is famous for being skeptical of “ideologies” because after studying the problem of evil he concluded that people only do the really evil stuff if they are infected with some ideology. I think he is (mostly) right about that. But if he’s right, so are the postmoderns, and we can be justifiably confused.

If you think about it, it is almost true by definition that they only thing that can get us to act against our interest is a replicator that we don’t identify with sufficiently enough to consider it “ours”. In the Bible they are mostly interested with the problems with having basic replicator drives like greed and lust. If we don’t identify with these replicators, it looks like they are getting us to do things we don’t like (see also, Schopenhauer). But now “we” (if we can even define ourselves) are sandwiched between low level drives and high level ideologies that are both vying to manipulate our decisions.

Metanarratives Solve Coordination Problems

But let’s be honest. Metanarratives aren’t all bad. They can solve coordination problems, and this can explain at least part of their success as replicators.

What do I mean by this? Well, let’s go back to the two kinds of coordination problems: inter-temporal and inter-personal. Metanarratives can help solve inter-temporal coordination problems, especially intergenerational ones.

Imagine part of your metanarrative is that god is always keeping a tally of your “good” and “bad” actions. This can help you avoid risky behavior that is bad for society overall, and for your future self/family in particular.

An even more obvious example is that if part of your narrative is that you are fighting for the glory of you nation you might be willing to, you know, fight for the glory of the nation and sometimes this might lead to an increase of, say, national glory.

Default Mode Network

I recently wrote a post about various theories of the brain, and one of these theories (the triple network model) features something called the Default Mode Network (DMN). The DMN basically helps you create your personal narrative. But (I believe) it also serves as kind of a god-simulator that judges all of our actions (i.e., the superego).

So that which we might attribute to a “metanarrative” might just be a rationalization of our own internal simulator. And that thing has been evolving for a long time. It’s DNA, not memes. We probably wouldn’t have one of the most substantial parts of our brain dedicated to imagining that god is judging us if “metanarratives” didn’t serve any evolutionary purpose.

Men Evolve (to be stupid) as Populations

At this point let me remind you that we evolve as populations, not individuals. In fact, we don’t even have DNA from most of our ancestors!

Humans evolve as populations, not as individual replicators. So we should imagine that many of our programs, the very deepest ones, aren’t really there to serve our individual interests. So, you think it’s weird that young men are eager to enlist and go out and fight wars for national glory? Think the only way you could get someone to risk their life (the very most important thing they have!) is to infect them with some malicious code from the elites? Wrong!

Young men want to fight and die in wars because it doesn’t take many young men for human populations to replicate. In our evolutionary history, tribal glory (combined with the evolutionary prospects of becoming a warlord and having Genghis Khan-level reproductive success) mean that our very own DNA encourages to take insanely stupid risks that might not make any sense from a selfish rational actor point of view.

So yeah, we can’t blame all the stupid shit on metanarratives.

The Meta Modern Meta Dilemma

So with all of this in mind, what are we to do?

The postmoderns ruined all our metanarratives, so us meta-moderns have to build new ones. The trouble is, if we can build our own meta-narratives, how should we build them. Don’t we need a meta narrative as a framework to tell us what kind of narrative to build? Yes, yes we do.

And I have a proposal: the fusion meta-narrative.

You see, if we exist like a vector super-position of many replicators, one big problem is that we are at risk of becoming completely incoherent. First we take some inexplicable action based on some hidden cultural program, then we get derailed by some primal directive…

We have plenty of paradoxical programs floating around in our consciousness, so the last thing we need is a new metanarrative that adds to the conflict. What we need is something to help smooth out the conflicts between existing aspects of our consciousness.

To be honest this is too hard of a task, and our ability to do it comes too late. Our core beliefs are probably with us by the time we are 12 (the exact number doesn’t really matter…just that it’s much younger than I am). We can deconstruct beliefs after that, but it’s too late to build new ones. So what we can do is simply try to manage the conflict among our many agendas, many of them hidden even from ourselves.

At first it might seem to be a downside that this metanarrative (i.e., trying to manage infighting among the shards of our consciousness) is too small. It doesn’t seem quite as glorious as fighting a war against the Great Satan. But it might just be an effective replicator. In fact, it might just be so effective that a healthy fusion meta-narrative might just become the dominant eigenvector…the secret to eternal life.